Bonneterie-librairie, rue des Ecouffes, Paris, photographie, vers 1910

Bonneterie-librairie, rue des Ecouffes, Paris, photographie, vers 1910

Although the first Jewish periodical was published in Judeo-Spanish in Amsterdam in 1675, the Jewish press did not begin to flourish until the 19th century. In Western Europe, the Emancipation prompted publications in the language of the country, such as Les Archives israélites de France (1840-1935) and L’Univers israélite (1844-1940) in France, the Jewish Chronicle in England (founded in 1841), and Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums (1837-1922) and Jüdische Presse (1869-1923) in Germany. But it was in the Russian Empire, where most Jews lived, that the Jewish mass press developed. The first significant newspapers, Ha-Maggid (1856-1891), Ha-Melitz (1860-1874) and above all Ha-Shiloah (1896-1919), edited by Ahad Ha’am, were published in Hebrew, the language of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment). In the Diaspora, Hebrew press publications proliferated but on a small scale, and it was only in Palestine that the Hebrew press attained large circulations. The first daily, Ha-Or (1910-1915), was published by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda. The major Hebrew dailies appeared later: Ha-Aretz, Davar (Labour Party), the orthodox Ha-Tsofeh and Yediot Aharonot.

It was in Yiddish that the press in the Diaspora became a mass media. When Ha-Melitz published a supplement in Yiddish Qol Mevaser, in 1862, its circulation grew considerably. The first Yiddish daily, Der fraynd (Saint Petersburg then Warsaw, 1903-1913) was read throughout the Russian Empire. Soon other newspapers began catering for more local readerships. In Warsaw, there were two fiercely competing dailies, Haynt (1908-1939) and Der moment (1910-1939).

Between the two world wars, there was a Yiddish press on the five continents, with major dailies such as Di presse (Buenos Aires) and Parizer haynt and Di naye presse (Paris). It reached its peak in New York in the early 1920s, where Der tog, Morgn-zhurnal, Frayheyt and above all Forverts had a total circulation of 500,000. The Hebrew and Yiddish press played a crucial role in the development of modern Jewish literature. It published novels in instalments and the supplement on Shabbat had a large poetry section. The Jewish communities in Greece, Turkey and the Balkans established a Judeo-Spanish press which, although much smaller than the Yiddish press, expressed great political and social diversity until the Second World War. Today most of the Diaspora press is published in the language of each country. After the disappearance of Undzer vort, the last Yiddish daily, published in Paris, in 1996, there are now some thirty Yiddish periodical throughout the world.

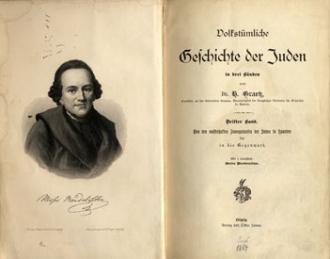

Heinrich Graetz (Xions, 1817 - Munich, 1891) Geschichte der Juden (Histoire des juifs), Leipzig, 1864

The Jewish scholar is traditionally a commentator on the sacred texts, not a historian. History of the Jews by Heinrich Graetz (1817-1891), published from 1853 to 1876, was the first attempt to reconstruct a Jewish past in the spirit of the Wissenschaft des Judentums (Science of Judaism), the movement that developed in Germany from 1817 onwards. Employing philological and critical methods, Graetz regarded the history of the Jewish people as that of a living body, as a continuum. Drawing on previously neglected sources, he showed great historical intuition and highlighted little-known episodes. Although educated both in Orthodox Judaism and the rationalism of the Enlightenment, he had difficulty in understanding the mystical movements – Qabbalah and Hasidism – and took little interest in the Jews of Eastern Europe, whose language, Yiddish, he regarded as a jargon unfit for expressing ideas.

The historian Simon Dubnow (1860-1941) drew more on social and economic history. Born in Byelorussia into a family of rabbis hostile to Hasidism (Mitnagdim), initially he developed ideological affinities with the cultural Zionism of Ahad-Ha’am. He took an interest in aspects neglected by the Science of Judaism, such as the Sabbatean and Frankist messianic movements – Jacob Frank (born in 1726 in Korołówka, died 1791 at Offenbach am Main) claimed to be a reincarnation of the self-proclaimed Messiah Sabbatai Zevi. An admirer of the Enlightenment, Dubnow developed a secular vision of Jewish history, and in Letters on Old and New Judaism (1897-1907), advocated the idea of a Jewish nation representing “the highest stage of cultural-historical individuality.”

Between the two Russian revolutions, convinced that the Jews had to fight simultaneously for both their civic and national rights, Dubnow founded the Folkspartei (Jewish People’s Party) demanding cultural autonomy within Russia, and co-founded the creation of the Jewish Literature and Historical-Ethnographic Society. In his History of the Jews in Russia and Poland (1916-1920), and in his monumental World History of the Jewish People, written from 1914 to 1920, he developed the idea of cycles of cultural hegemony successively exercised by the Jewish communities in Babylon, Spain, Poland and Lithuania. Dubnow was the first to consider Jewish history as part of world history. Against “the resurrection of a Jewish State in Palestine” and assimilation, he saw Yiddish as the language of the renaissance of Jewish culture, and cofounded the Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut (YIVO) in Vilnius in 1925. For Dubnow, historical research and Jewish thinking are indissociable. In December 1941 he was murdered by a Latvian policeman during the extermination of the Riga ghetto.

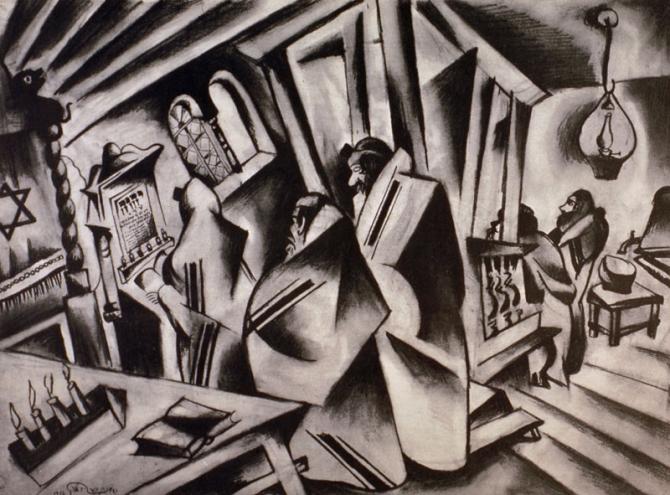

Issachar Ber Ryback (Iélisavelgrad (Russie), 1897 - Paris, 1935), illustration extraite de Shtetl, Berlin, 1923

The Yiddish language was first spoken in the 10th century in the Rhine and Moselle valleys and spread in successive waves until, at the beginning of the 18th century, it became the vernacular language of the Ashkenazi Jews from Amsterdam to Venice and from Mulhouse to Riga. The Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment) in Western Europe in the 18th century, prompted a decline of Yiddish, but the ideas of the Haskalah did not spread to Eastern Europe until the 19th century. Despite their preference for Hebrew and Russian as cultural languages, some authors preferred to voice their social and cultural ideas in Yiddish. Yiddish was so entrenched in the population that from the 1870s a generation of intellectuals declared it worthy of being the linguistic vehicle of modern culture in the Jewish world.

Mendele Mokher Sforim (1835-1917), Yitzhok Leibush Peretz (1852-1915) and Sholem-Aleikhem (Sholem Naumovich Rabinovich, 1859-1916) were the founders of modern Yiddish literature. The quality of their writing and variety of their themes and forms (novel, short story, tale, poetry, theatre, essay, memoirs) and literary genres (comedy, tragedy, drama, satire), gave Yiddish literature its full richness and served as a reference for their successors.

As the Jews of Eastern Europe emigrated in waves from 1880 onwards, Yiddish culture spread to every continent. In Eastern Europe its major centres were Warsaw, Vilnius, Kiev, Chernivtsi, then Moscow, Lodz, Bucharest and the network of Jewish townships (shtetlekh), in the Americas (New York, Buenos Aires, Montreal), Palestine, and also Western Europe (Paris, London, Berlin, Vienna) and to some extent Australia and South Africa. An all-embracing culture, it pervaded every sphere of daily life: home, school, work, religion, organizations, politics and trade unions.

Yiddish culture reached its peak between the two world wars in independent Poland, where it was taught in a network of secular schools that grew to some two hundred in the 1930s. In the Soviet Union, Yiddish was rapidly promoted as the only authorised Jewish language, to the detriment of Hebrew. Soviet Yiddish culture flourished in the 1920s but declined from the 1930s onwards and was prohibited in 1952. Although tolerated again from the 1960 onwards, it remained a minority language. Linguistic assimilation in Western Europe and America, the Shoah in Eastern Europe and Stalinism in the Soviet Union prompted the decline of Yiddish culture. The language of revolutionaries and the avant-garde in the 1920s, after the Second World War and particularly in Israel it was regarded as a culture of the past, of the world before the Shoah.

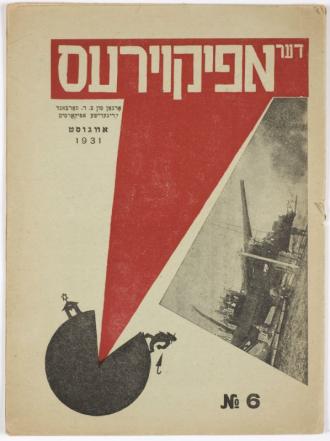

Der Apikoyres [Le libre penseur] n°6, Moscou, 1931

The development of Yiddish periodicals in the 20th century can be traced back to the publication of Qol Mevasser, founded by Alexander Zederbaum (1816-1893) in Odessa in 1862. Initially a supplement of the Hebrew weekly Ha-Melitz, then an autonomous review from 1869 to 1872, Qol Mevasser sought to disseminate the ideas of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment), and militated in favour of modern Jewish culture and the recognition of Yiddish as a literary language. It did much to promote the work of the first modern Yiddish writer, Mendele Mokher Sforim. At the turn of the century, Yiddish periodicals embraced all forms of literature and published both translations of the great European writers and original works in Yiddish. They always bore the mark of their eminent editors: Sholem Aleikhem for Yudishe folks-bibliotek (1889-1890), Yitzhok Leibush Peretz for Yudishe bibliotek (1891-1904) and Yontef-bletlekh (1894-1896), and Mordkhe Spektor for Der Hoyz-fraynd (1887-1896).

Yugnt was the first magazine whose writers contributed their work collectively (New York, 1907). Emblematic of the Di Yunge movement, it was influenced by the Symbolists and advocated art for art’s sake. As a showcase for literature but also painting, music and sculpture, it reflected the synthesis between the arts then underway in modern art in Europe and the United States. In Russia after the October Revolution, Eygns (Kiev, 1918-1920) Baginen (Kiev, 1919) and Oyfgang (Kiev, 1919) were published. In the fledgling Republic of Poland, Yung-yidish (Lodz, 1919), Khaliastra (Warsaw, 1922; Paris, 1924), Ringen (Warsaw, 1921-1922) and Albatros (Warsaw, 1922 ; Berlin, 1923) appeared. In Western Europe, émigré Yiddish intellectuals created Renesans (London, 1920), Milgroïm (Berlin, 1924) and Literarishe revi (Paris, 1926). In the United States, Di Yunge pursued their activities with Shriftn (New York, 1912-1925), but they were eclipsed by a new group of writers and poets who published In zikh (1920-1939).

The avant-garde experiments of the 1920s were superseded by more long-lasting publications. Between the wars, the socialist monthly Tsuqunft, founded in New York in 1892, and the weekly Literarishe bleter (Warsaw, 1924-1939), both of extremely high quality, were the two most influential reviews in the Yiddish world. Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union, Yiddish writers completely cut off from the western world published in Di royte velt (Kharkov-Kiev, 1924-1933) and Der shtern (Minsk, 1925-1941). The publications that had a profound impact on Yiddish life after the Shoah are Yidishe qultur, created in New York in 1938 by the communist organization Ikuf, Sovetish heymland (Moscow, 1962-1991), the only concession the Soviet regime made to Yiddish culture, and above all Di goldene qeyt (Tel Aviv, 1947-1995), founded and edited by Abraham Sutzkever, the great poet and hero of the Vilnius ghetto.

Les Voyages de Benjamin III, Goset (théâtre yiddish), photographie, Moscou, 1927

From the Middle Ages onwards the celebration of Purim included a farcical, parodic performance of the story of Esther called the purim-shpil. In the course of time, the badhen (comedian and storyteller), letsim (jesters) and katoves shreiber (humourists) became familiar popular figures who handed down their skills from father to son. In Tsarist Russia, this folk theatre evolved under the influence of the proponents of the Haskalah (maskilim). The plays with which the maskilim endeavoured to spread the ideas of the Enlightenment were virulent critiques of the world of the rabbis and the hasidim. In 1862, Abraham Goldfaden (1840-1908), father of modern Yiddish theatre, performed for the first time in the leading role of one of these plays, Serkelede, by Shloyme Ettinger (1802-1856). At that time, performances by troupes of singers, dancers and mimes, known as Broder Singers, were hugely popular in Jewish provinces in southern Russia.

From the 1880s onwards, pogroms and discriminatory measures prompted a huge wave of emigration to the United States and New York became a vibrant centre of Yiddish theatre. Abraham Goldfaden worked successfully as a stage director, theatre director and songwriter. Jacob Gordin adapted Shakespeare and Goethe and staged his psychological dramas Mirele Efros and God, Man and Devil. This period also saw the creation of a whole repertoire of popular melodramas and comedies.

Classical Yiddish authors also wrote for the theatre and left their mark on it: Sholem Aleikhem’s visions of a Jewish world confronted with modernity and his picturesque, engaging characters greatly influenced Yiddish playwrights, Mendele Mokher Sforim with The Tax and the burlesque Travels of Benjamin III, which lent itself to avant-gardist productions, and Yitzhok Leibush Peretz with The Golden Chain (1909) and A Night in the Old Market (1915), two of the darkest and most profound plays in the Yiddish repertoire. Symbolist and expressionist aesthetics, explorations of new forms of expression by the modernist Yiddish poets and the influence of Stanislavski’s theatrical realism fueled theatrical experimentation in the interwar period. Everywhere in Europe, theatres were playing a rapidly diversifying Yiddish repertoire. In 1920 the Vilna Troupe, founded in 1916, premiered Der Dybbuq by An-sky (Shloyme Zanvl Rappoport, 1863-1920), which became a stage and screen classic. After the Russian Revolution, the Yiddish theatre underwent an unprecedented growth that culminated in the creation of the Moscow State Jewish Theatre, directed by Alexei Granovsky (1890-1937). Two exceptional actors, Solomon Mikhoels and Veniamin Zuskin, stage sets by Chagall and a repertoire ranging from Sholem Aleichem to Peretz Markish made it one of the legendary Yiddish theatre companies. Mikhoels and Zuskin were assassinated in 1948 and 1952 respectively, and the Soviet regime, having eliminated a number of pre-war Yiddish authors, put an abrupt end to this experience.

The vitality of the Yiddish theatre was such that it was performed in the ghettos and sometimes even in the camps during the Second World War. And today the Yiddish repertoire continues to be performed in the United States, Tel Aviv, London, Buenos Aires, Melbourne, Montreal and Paris.

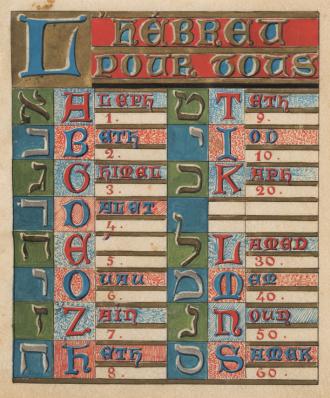

L'hébreu pour tous, livret manuscrit, XXe siècle

To talk of a language’s “renaissance” is to consider, at least metaphorically, that it was “dead” at a given moment in its history. But, between the end of the Mishnah period (early 3rd century BCE) and 1879, the year the first article by Eleizer Ben-Yehuda was published, one cannot say that the Hebrew language was dead because it was used as a scholarly, community and liturgical language. As the vector of a major corpus of religious, poetic, scientific and philosophical literature, it was unquestionably “alive” because it underwent influences – particularly that of Arabic in the Middle Ages – and was enriched with neologisms. On the other hand, it was no longer a spoken language, and although it was occasionally used as a means of communication between Jews from different diasporas, the language they were speaking was no longer their mother tongue.

Hebrew therefore had to be “brought back to life” as a spoken language. The first to attempt this were the proponents of the Jewish Enlightenment (maskilim) in the mid-19th century. But by basing this revival solely on biblical Hebrew, which has a vocabulary of only eight thousand words and lacks many terms indispensable for everyday communication, the maskilim were condemning their initiative to failure. The lexicographer and newspaper editor Eliezer Ben-Yehouda

(Eliezer Yitzhak Perlman Elianov, 1858-1922) tirelessly endeavoured to make Hebrew a true language of verbal communication. He insisted that his wife speak only Hebrew to their son, born in 1882, who thus became the first child to speak the language as a mother tongue. Relying on a network of teachers at the Alliance Israélite Universelle to educate a generation of Hebrew speakers, he compiled a monumental dictionary and forged numerous neologisms. The obstacles he had to overcome were the incompleteness of the sources (Bible, Talmud, medieval texts), the indifference of many Yiddish-speaking Jews, and the Orthodox community’s hostility to a profane use of a sacred language. In 1890, Ben-Yehuda created the Va’ad ha-lashon ha-‘ivrit (Committee of the Hebrew Language, which became the Academy of the Hebrew Language in 1953), a group of linguists and writers charged with deliberating on the delicate questions of pronunciation (Ashkenazi or Sephardi) and the choice between competing forms from different historical strata. For the lexicon, Ben-Yehuda borrowed from other languages (notably Arabic) and above all reactivated linguistic roots attested in ancient strata of Hebrew. Thus from millah (“word” in biblical Hebrew) and sha’ah (“hour” in Mishnaic Hebrew) he created millon (dictionary) and sha’on (wristwatch).

The Academy continues today to create neologisms based on historical and linguistic research and attempts to set norms. But in parallel to this interventionist approach, modern Hebrew is a living, naturally evolving language whose spoken usage is constantly becoming richer and more diversified (familiar language, slang). This successful transition from the written to the spoken is unique in the history of the world languages.

Bundistn, Textes de Yekov Pat, illustrations de Henrik Berlewi, Varsovie, 1926

Apart from Zionism, the principal exclusively Jewish political movement was the Bund (General Jewish Labour Bund in Lithuania, Poland and Russia), founded in Vilna (Vilno in Yiddish) in 1897. A Marxist-inspired socialist party, it owed its existence to the growth of the Jewish proletariat in the 19th century. Fiercely opposed to Zionism, Bundism advocated doikayt (literally “hereness” in Yiddish, i.e. action here as opposed to aspiration to a future elsewhere) and, in response to anti-Semitism in Tsarist Russia, Jewish political autonomy. It promoted Yiddish as the national Jewish language.

The Folkspartei, founded in Russia in 1906 by the historian Simon Dubnow, demanded Jewish political and cultural autonomy but did not share the Bund’s Marxist ideals. In independent Poland from 1918, the Folkspartei took part in the Yiddishist movement, notably in the creation, with the Bund and the leftist Poalei Zion (Lovers of Zion) movement, of the Tsysho (Central Yiddish School Organisation).

In reaction to these secular movements, the Orthodox Jews created the Agudat-Yisrael party in 1912. Significant ideological differences became apparent between the German Orthodox Jews, who accepted European culture, and the Eastern European Orthodox community, which denied the existence of secular culture. At the same time, a strong assimilationist trend was changing the Jewish world, either politically unmotivated or via the massive Jewish adherence to the Communist movement.

Helmar Lerski (Strasbourg, 1871 - Zürich, 1956), Ecole agricole pour jeunes filles, Village de Nahahal, photographie, Palestine, années 1930

Zion has always been at the heart of the Jewish prayers and dreams. In the 18th century the rabbis Judah Alkalai and Zvi Hirsch Kalischer turned to Messianism to exalt the return to Jerusalem and the Promised Land. Zionism cannot be comprehended without this root in tradition. Yet it was a socialist philosopher influenced by Marx and Engels, Moses Hess (1812-1875), who imagined the return to Zion (Rome and Jerusalem: The Last National Question, 1862). The modern, political form of Zionism emerged in the second half of the 19th century, as a result of the combined effects of the Emancipation and the upsurge in nationalisms and anti-Semitism. While assimilation progressed in Western Europe, the situation of the Eastern European Jews in the “Pale of Settlement” (the western region of Imperial Russia where the Jews were confined by the Tsarist authorities from 1791 to 1917), threatened with expulsion and subjected to discriminations, grew constantly more dire. After the assassination of Alexander II, persecutions and attacks culminated in the violent pogroms of 1881-1884, which unleashed massive waves of emigration. In 1882, Leo Pinsker published his pamphlet Auto-Emancipation, the first political formulation of Zionism, in which he advocated the construction of an autonomous and independent national existence. One of the various groups in which these ideas were circulating, the Odessa Committee of the “Lovers of Zion” (Hovevei Tsiyon), lastingly influenced Russian Zionism. The first wave of emigration to Palestine (the First Aliyah, 1882-1903) came with the Bilu (Palestine Pioneers), a group of university students in Kharkov influenced by Russian populism whose goal was to revive the Jewish nation by the agricultural settlement of Palestine, who created the first farming colony, Rishon LeZion.

In Western Europe, the Emancipation had won the Jewish intellectual elite over to liberal ideas. The pioneering Zionism of the journalist, playwright, writer and proponent of the Jewish Enlightenment Theodor Herzl (1860-1904), born into an assimilated family in Budapest, was a reaction to anti-Semitism. Witness to the election of the anti-Semite mayor of Vienna Karl Lueger and the public humiliation of Captain Dreyfus amidst cries of “Death to the Jews!” he wrote Der Judenstaat (The State of the Jews) in 1896 and organized the first Zionist congress in Basle the following year. Convinced that only the creation of a state, guaranteed by law and international agreements, could save the European Jews, Herzl insisted on the political and diplomatic aspect of this edification. The leading opponent of this was Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (1856-1927), known as “Ahad Ha’am,” ideologist of the Hovevei Tsiyon (Lovers of Zion) movement, who saw the land of Israel as the centre of the spiritual and cultural revival of the Jewish people. Herzl founded the World Zionist Organisation, an amalgam of numerous parties and factions. In 1903-1905, Menachem Ussishkin (1863-1941), a “practical Zionist,” and Ahad Ha’am opposed the “Uganda Plan,” a British proposal accepted by Herzl. After Herzl’s death in 1904, Max Nordau (1849-1923) took over as head of the Zionist movement. The creation of the Jewish National Fund (Qeren Qayyemet le-Yisrael) or KKL in 1901, vital for the purchase and clearing of land, and the foundation in 1925 of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem were vital additional stages in the realization of the Zionist ideal.

After the Sykes-Picot Agreement in 1916, dismantling the Ottoman Empire and dividing Palestine into British and French mandates, the Balfour Declaration in 1917 stated that the United Kingdom viewed favourably “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” The Second Aliyah (immigration wave in 1905-1914) and the third (1919-1923) profoundly transformed the Yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine). Inspired by the ideas of Nachman Syrkin (1868-1924) and Ber Borokhov (1881-1917), the Labour Zionists asserted themselves as the movement’s principal political and social force. They formed the Haganah (the first defense organization) and the Histadrut (General Organization of Workers in the Land of Israel), founded in Haifa in 1920 and embryo of the institutions of the future state of Israel. From the 1920s onwards, the Yishuv had to face the hostility and sporadic rioting of the Arab population, which culminated in the explosion of violence in 1929 and the uprising in 1937-1938.

Under Arab pressure, the British restricted Jewish immigration (1931 and 1939 white papers). The Revisionist Zionists led by Ze’ev Jabotinsky (1880-1940) and the Irgun, their military organization, called for implacable combat against the British occupier. The extermination of a third of the European Jews by the Shoah precipitated the foundation of a Jewish state. The plan to divide Palestine voted by the United Nations on 29 November 1947 was immediately rejected by the Arabs. In Tel Aviv on 14 May 1948, David Ben-Gurion (1886-1973) proclaimed the independence of the State of Israel. The next day, five Arab armies invaded the new state.

An idea of a nation that had taken shape in the minds of a few visionaries in Europe had been transformed into a geographical reality in the Middle East.

Abel Pann (Kreslawka (Lettonie), 1883 - Jérusalem, 1963), Adam et Eve, lithographie, Paris, 1916

“We are slaves in many countries […]. Deep in our hearts, we have no land, no sky. A national art, in the broadest sense, can flourish only on Jewish soil.” Martin Buber

In 1903, Boris Schatz, a Lithuanian-born sculptor with Zionist ideals, proposed to Theodor Herzl his project to create a school of arts and crafts in Palestine with two missions: to encourage the birth of a Jewish art rooted in the ancient history of the Jews, and to create craft industries to improve the economic and social situation of the Jewish community, the Yishuv. The project was adopted by the 7th Zionist Congress in Basle. The Bezalel Academy, named after the first Hebrew artisan, Bezalel ben Uri ben Hur, builder of the Tabernacle in the desert, opened in Jerusalem in February 1906.

From the outset, it comprised a museum of masterpieces of Jewish art, archaeological collections and local flora and fauna, a school of fine art, and workshops where artisans of all ages could produce objects from students’ drawings.

These workshops gradually diversified to include carpet weaving, silverware, damascening, marquetry, pottery, etching, photography, etc. This production featured widely abroad in exhibitions and albums.

The academy’s successive teachers, Ephraim Moses Lilien, Samuel Hirszenberg, Ze’ev Raban and Abel Pann, all European in culture, sought to provide Zionism with powerful symbols, found in the Bible and in the victorious episodes of Jewish history. The Bezalel style was an encounter of western art, particularly Art Nouveau, and images of a mythical Orient.