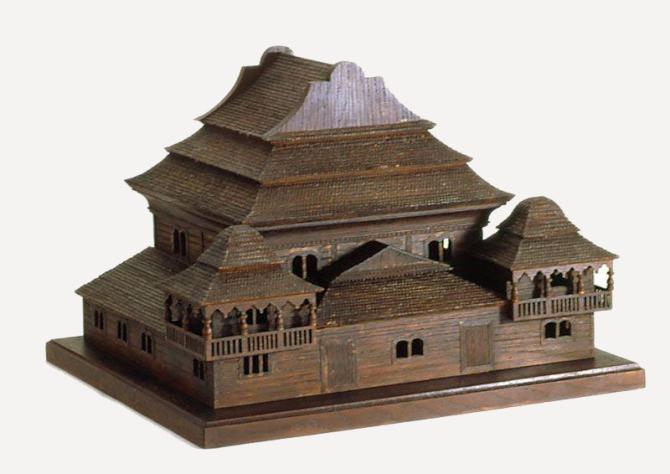

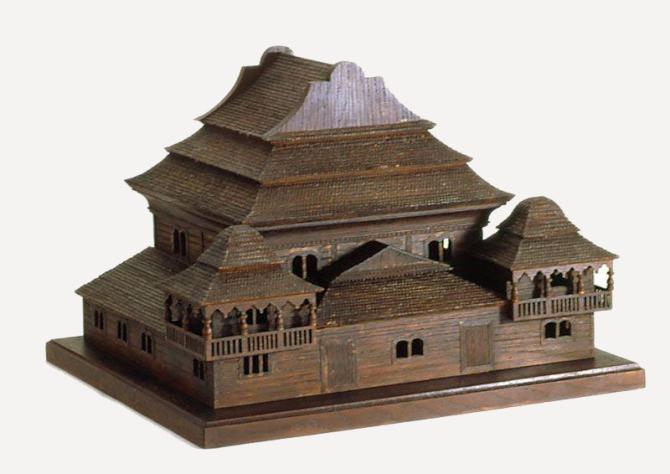

Maquette de la synagogue de Wolpa (Biélorussie), réalisée par les élèves des écoles de l'ORT de Constantine ou d'Alger vers 1950 ou 1952

Maquette de la synagogue de Wolpa (Biélorussie), réalisée par les élèves des écoles de l'ORT de Constantine ou d'Alger vers 1950 ou 1952

The wooden synagogues built in Poland, Ukraine and Lithuania in the second half of the 16th century and in the 17th century constitute a remarkable phenomenon in traditional synagogue architecture, both in the unity of their style and the intense artistic creativity lavished on their decoration. Although their architects were inspired by local wooden constructions, particularly churches, they gave them distinguishing features, particularly their two or three-tiered pagoda-like roofs, structured by their often visible timber frame. The synagogues at Wolpa in Belarus and Zabłudów in Poland are very typical of this architecture.

These synagogues had a vast, two-storey, square or rectangular interior space for men only, and one or several annexes for women and community activities. Unlike their austere exteriors, their interiors were ornately decorated with polychrome paintings, inscriptions and sculpted wooden decorations, influenced by Italian Renaissance in the most ancient, and by baroque art in the more recent. The nave was surmounted by a wooden cupola supported by pillars, its vault decorated with animal and floral motifs and the signs of the zodiac. The raised area in the middle (almemor or bimah) was surrounded by a balustrade with straight or cabled columns supporting a dome with sculpted wooden arcades. Against or inset into the east wall, stood the Torah Ark (aron qodesh), in wood sculpted with traditional motifs such as the tables of the Law, the lion, crown, temple and blessing hands. Most of the wooden synagogues were in small towns or villages and were modest in size, but the city synagogues were much more imposing, stone edifices. Usually built outside the city walls, these buildings resembling fortresses, with flat roofs and crenelated parapets, provided safe havens during pogroms and wars and could also be used as prisons by the local authorities. In the main room, the bimah was set in an architectural structure with four tall pillars, one of the characteristics of the fortress synagogues.

Almost all these wooden synagogues were destroyed during the First and above all the Second World War. Several of the more solid fortress synagogues, including the Old Synagogue in Krakow, have survived.

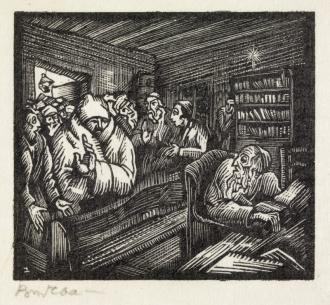

Joseph Budko (Plonsk (Russie), 1888 - Jérusalem, 1940), illustration pour les Légendes hassidiques de Samuel Lewin

Berlin, vers 1923

In Podolia in the 18th century, a rabbi, Israel ben Eliezer (1700-1760), roamed the woods and villages celebrating the presence of God, giving advice and dispensing his herbal remedies. His saintliness and piety earned him a “good reputation” (Baal Shem Tov in Hebrew), hence the acronym Besht by which he is more widely known. He sought to celebrate and serve God joyfully at all times. Dedication (devequt) to God is the vocation of all men who believe that the entire universe is filled with His presence.

The Besht did not make long speeches, put forward grand principles or make threats. Instead, he told wonderful stories to encourage his audiences to devote their existence to the celebration of God. His first disciples formed small communities whose members (hasidim) venerated their spiritual leader, the Righteous (Tzaddiq), relying on his mediation to pursue their path on earth and earn their place in heaven. They sought his advice and company and treated him with great deference, like a prince. Soon, all over Eastern Europe, new masters created new communities, recruiting their disciples from the working classes racked by misery and the wait for the Messiah. Hasidim found consolation and a vocation in this new religious movement promoting ideals of piety and enthusiasm: their exacting and exalting mission was to rekindle through prayer the sparks of divinity exiled and dispersed with the people of Israel and restore its brilliance and reign in the world.