Arche sainte, Modène, 1472, noyer sculpté, marqueté et peint, garniture en velours et soie, 265 x 130 x 78 cm

Dépôt du musée de Cluny, musée national du Moyen Âge, Paris, collection Strauss, don de Charlotte de Rothschild

Arche sainte, Modène, 1472, noyer sculpté, marqueté et peint, garniture en velours et soie, 265 x 130 x 78 cm

Dépôt du musée de Cluny, musée national du Moyen Âge, Paris, collection Strauss, don de Charlotte de Rothschild

When the Persian king Cyrus the Great decreed in 538 BC that the Jews, held captive in Babylon since 585 BC, could return to Palestine, they took with them their custom of meeting to pray and hear the reading of the Law in assemblies of at least ten men (minyan). For several centuries this form of worship coexisted with the service in the Temple and continued alone after the Temple’s destruction by Titus in 70 AD. As places of prayer and study, synagogues became the centre of community life in the diaspora. Despite strong local influences, elements of the synagogue remain often the same: they face east towards Jerusalem, and their interior layout is organised around the liturgy’s two focal points: the Torah Ark (heikhal or aron qodesh) and the raised platform on which the Torah is read (bimah).

The congregation faces the east wall, where the Torah Ark contains the Torah scrolls (Sefer Torah, plural Sifrei Torah). It can be built inside a cavity in the wall, or standing as a large closet or chessboard. It is often concealed by a curtain, the parokhet. The lectern or table for reading the Torah (bimah) is in the middle of the room, on a platform. The male congregation sits on benches on either side and the women pray in a gallery above or in the side-aisles but do not take an active part in the liturgy. Although the Talmud states that the synagogue must be taller than the surrounding buildings and have windows enabling worshippers to see the sky, from the Middle Ages onwards the urban density of Jewish quarters usually prevented this.

Until the 18th century, the exteriors of European synagogues remained modest due to constraints imposed by the Church. From the Renaissance onwards, the Torah Ark became the central element of the synagogue’s interior architecture, sumptuously decorated and further enhanced by ornate curtains.

Marco Marcuola (Vérone, 1740 - Venise, 1793), Un mariage juif, Venise, vers 1780

Marriage is the purpose of divine creation: it is said in the Talmud that once God had created the world He devoted his time to forming couples. In the Bible, conjugal love embodies sacred perfection and is a metaphor of the union between God and his people, between Israel and the Torah. The marriage ceremony can take place in a house, outdoors or in a synagogue. In its rabbinic form, the ceremony has two stages. It begins with the betrothal, called erusin or qiddushin, in which the groom takes the bride as his wife before two witnesses and in the presence of ten men. To seal the qiddushin, he gives her money, an object of value or a document stating his intention to marry her and declares: “Behold you are consecrated to me with this ring according to the laws of Moses and Israel” (the wedding ring did not become part of this ritual until very late on). Next comes the reading of the nuptial agreement (ketubbah), stating the groom’s responsibilities to his bride in the case of divorce or widowhood. When this contract has been signed by the groom and the witnesses, the marriage proper (nissuin) begins. The seven blessings (sheva berakhot) are then recited beneath a dais (huppah) representing the roof of a house over the couple. At the end of the ceremony the groom breaks a glass in memory of the destruction of the Temple. The ceremony ends with the couple spending a short time alone together.

The marriage celebrations can then begin. Since Antiquity, each stage of these festivities is ritually accompanied by music, chants, dances and amusements. The art of decorating marriage contracts reached its virtuoso peak in Italy in the 17th and 18th centuries.

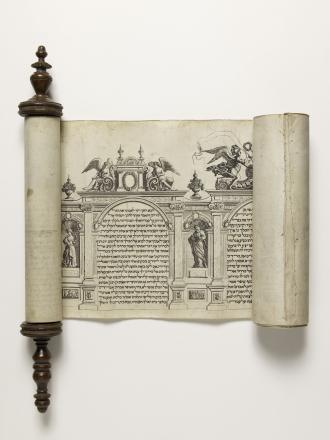

Rouleau d'Esther enluminé, attribué à Shalom Italia (Mantoue, vers 1619 - Amsterdam, vers 1655), Amsterdam, vers 1641

Purim is celebrated on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar. It commemorates the saving of the Jews from a plot to exterminate them. This episode, which took place in the ancient Persian city of Susa (Shushan) in the 5th century BC, is recounted in the Book of Esther (Megillat Ester). Haman, vizier to King Assuerus (Ahashverosh, identified as Xerxes I), decided to kill all Jews “young and old, children and women,” and cast lots (“pur” in Akkadian, origin of the word purim) to choose the date on which to carry out his plan: 13 Adar. Implored by her uncle Mordekhai, a descendant of King Saul, Queen Esther persuaded her husband Assuerus to counter the plot. The Jews then defeated their enemies throughout the kingdom and Haman and his sons were hanged.

The sages instated a day of fasting on 13 Adar. 14 Adar is a day of rejoicing. In cities that were walled in ancient times, the feast is held on the next day and is called Shushan Purim. On the eve and morning of the feast the Book of Esther is read from a calligraphed parchment scroll (the megillah) in the synagogue. The congregation shakes rattles to drown out the name of Haman, enemy of Israel, every time it is read. The celebration ends with a feast, at which guests are invited to drink wine until they can no longer distinguish the names Haman and Mordekhai. Delicacies and pastries are offered to friends and gifts to the poor, people dress up in costumes and plays are performed. Illuminated megillot for private use, either hand-decorated or printed, appeared after the Renaissance. All are repetitively embellished with engravings of ornamental figures and motifs, delimiting, between columns and cartouches, the space in which the text is calligraphed. Italian scrolls are markedly influenced by commedia dell’arte.

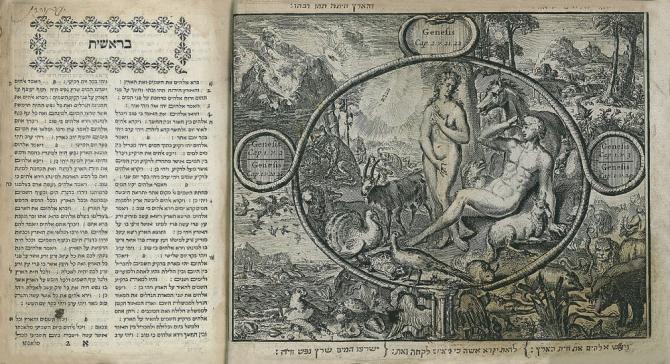

Hammishah Houmshei Torah, Bible publiée par Menasseh Ben Israël (Madère, 1604 - Midelburg, 1657), Amsterdam, 1630-1631, illustrations de Romeyn de Hooghe (Amsterdam, 1645 – Haarlem, 1708), gravures insérées après 1712

Hebrew printing developed in Italy, Central and Eastern Europe and the Netherlands from the 15th to the 18th century. Although major dynasties of printers established themselves, the profession was hampered by censorship, insecurity and itinerancy. France very nearly became the cradle of Hebrew typography – a contract was drawn up in Avignon in 1443 for the supply of a Hebrew typeface. But it was in Italy, at Reggio di Calabria in1474, that the first book was printed in Hebrew: Rashi’s commentary on the Pentateuch. Printing in Spain and Portugal, interrupted by expulsions, was sporadic at best. Yet the first Hebrew presses were established in these countries, and the Pentateuch was printed in Hebrew at Faro in 1487, eight years before the printing of the first book in Latin. At Fez in Morocco exiles published the first book printed on the African continent, and the Soncino, Conat and Günzenhauser families established themselves in Italy.

In 1484 Joshua Solomon Soncino published the Berakhot tractate of the Babylonian Talmud, then, in 1488, the first printed Hebrew Bible. In the Ottoman Empire, the brothers Nahmias and Sasson founded printing works in Constantinople in 1493, and at Thessaloniki in 1513. In 1512 a small Ashkenazi group created a printing works in Prague, where Gershom ben Solomon Kohen printed the first Haggadah in 1526. Their typography was greatly inspired by Italian typography. In 1605 the Bak family began printing in Prague. Not until the early 17th century were there printing centers in the German-speaking countries, such as Hanau and Sulzbach, where numerous translations and compilations were also printed in Yiddish. In Poland, from 1534, Cracow then Lublin became major printing centres. At the very beginning of the 16th century, close to the major theology faculties, Christian printers published books in Hebrew. In Basle, Heinricus Petrus and Johannes Froben employed Jewish and Hebrew-speaking Christian printers and copied their characters from Ashkenazi manuscripts. In Paris, the Estienne family used a new kind of typeface, produced by the engraver Guillaume Le Bé. The two Estienne Bibles are regarded as masterpieces of Hebrew typography. Le Bé also supplied foreign printers, including Plantin in Antwerp and Bomberg in Venice. The Frenchman Christophe Plantin established himself in Antwerp in 1549, where he published a Bible and Hebrew grammars and dictionaries. In Venice, from 1516 to 1549, Daniel Bomberg, from Antwerp, was the first to publish the Pentateuch (1517), two complete editions of the Talmud (1520 to 1523) that became reference works for printers and scholars, and the Rabbinic Bible (Miqraot Gedolot). Le Bé’s typefaces were subsequently adopted by presses in northern and eastern Europe. This virtuoso engraver – who sometimes signed his work “Gugliemus ha-Tzarfati” (Guillaume the Frenchman) – did much to establish the definitive form of the Hebrew and especially Sephardic letter. In Amsterdam in 1626 Menasseh ben Israel created the so-called “Amsterdam letters” (otiyot Amsterdam) that became the dominant typeface in Europe. From 1658 the Athias family published prestigious works, including the Amsterdam Haggadah in 1695. The Proops family, printers from 1704, published numerous liturgical works and established Amsterdam as a dominant Hebrew printing centre, rivalling Venice until the 19th century, when Poland and Germany became the most innovative and active centres.