Edouard Moyse (Nancy, 1827 - Paris, 1908), Une pâque juive au Moyen Âge, avant 1886

Edouard Moyse (Nancy, 1827 - Paris, 1908), Une pâque juive au Moyen Âge, avant 1886

The medieval Jewish community, the qehillah, established itself in Western Europe in the 10th century. Its organisation was different to that of ancient and oriental Judaism. From the 10th century on, Jewish settlements proliferated in northwest Europe as towns and cities grew and trade increased throughout the West. The first qehillot formed in the Rhineland, at Worms, Speyer and Mainz. Granted right of residence, they obtained charters guaranteeing them privileges and the protection of the local authorities. The earliest were granted by the bishop of Speyer in 1084. The qehillot were the result of both the pressure exerted by Christian authorities and the need for these urban minority groups to organise Jewish life.

The qehillah was the only interlocutor with the prince, emperor or bishop, included all the Jews in the same locality and had judiciary and fiscal autonomy. Only conversion to Christianity could remove an individual from its authority. It was regulated by a set of decrees (taqqanot) enacted locally but sometimes widely – the most ancient regulate the conditions of settlement (herem ha-yishuv). The qehillah was governed by an assembly (qahal), made of notables called parnasim, shivah tovei ha-’ir or gabbayim (depending on the time and place) and appointed by the assembly of taxpayers. A ruling by Meir of Rothenburg (13th century) clearly defines this assembly’s prerogatives and the principles governing its decisions.

The figure of the rabbi emerged in the medieval community. He was no longer merely a scholar or master, like the rav during the Talmudic period. His knowledge and authority enabled him to rule on liturgical controversies and establish the legitimacy of community orders. In the 13th century he became a professional, paid by the community. Rabbinic ordination (shmirah), obsolete since late Antiquity, reappeared in the second half of the 14th century, probably due to the demographic and institutional upheavals caused by the Black Death (1348).

Lampe de la Reconsécration, France, XIVe siècle

After the destruction of the temple and the city of Jerusalem by the Roman emperor Titus in 70 AD, and following the brutal repression of the Bar Kokhba revolt in Judea by the emperor Hadrian in 135, Jewish communities in the Roman Empire grew considerably. Jews settled in Mediterranean Gaul and along the Rhône and Rhine in the first centuries AD. There are records of their presence at Narbonne, Vannes, Clermont-Ferrand and Valence in the late 5th century. There is mention of a synagogue in Paris in 582, and another at Orleans in 585.

During the Merovingian period anti-Semitic policies led to a decline in Jewish settlements, but the Carolingian Empire (9th and 10th centuries) favoured their growth. Two distinct poles emerged and endured throughout the Middle Ages: in Provence and in Languedoc, where natural links with Iberian Judaism established themselves; and in northern and eastern France, where Rhenish and Italian influences were more dominant. The Jews could now exercise all professions and played an important role in trade between the East and West.

Following the division of the Carolingian Empire after the Treaty of Verdun in 843, the status of the Jews varied in principalities, seigneuries and the royal domain. Some regions granted communities favourable living conditions, guaranteeing them rights such as owning farms and vineyards. The writings of rabbi Salomon ben Isaac ha-Tzarfati (Rashi) of Troyes (1040-1105), particularly his commentary on the Talmud, still in use today, is the most brilliant example of the vitality of the Jewish communities north of the Loire, in the area known since that period as Tzarfat and demonstrates the specific acculturation of Jewish communities to the culture of this area.

The First Crusade (1096), less deadly in France than in the Rhineland, prompted outbreaks of violence against Jewish communities in Metz and Rouen. The first accusation of ritual murder in France was made in 1171 at Blois, where thirty-two Jews were tried, sentenced and burnt at the stake. The 13th century marked the beginning of a period of great insecurity for the Jews in France. The segregational measures taken against them by the Church, aided and abetted by secular powers, became more virulent. The wearing of a distinctive badge, the rota (wheel), imposed on Jews after the Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215) and reiterated by King Louis IX, known as “Saint Louis,” in 1269, rapidly spread to all Jewish communities in the Christian West.

The territorial expansion of the Capetian kingdom and its establishment of a centralised administration brought major changes for Jewish communities in France. The right of residence was now a privilege granted by the secular authorities. Restrictions and exclusions increased and Jews were confined to the financial professions. Treated as possessions or serfs, as “servants of the royal chamber” (servi camerae regis), they were exploited as a source of tax revenue. Intent on despoiling them of their possessions and the debts owed to them, King Philip Augustus expelled the Jews from the kingdom in 1182, then recalled them in 1198. In 1306, King Philip IV the Fair decreed the expulsion of the one hundred thousand Jews in his kingdom. This to and fro of expulsions and readmissions continued during the reigns of his successors, destroying all forms of community life. When King Charles VI decreed in 1394 that that no Jew could dwell in his domains, the ensuing expulsion affected an already greatly diminished population.

In the County of Provence, independent from the kingdom of France, the growth of communities (Marseille, Narbonne and Lunel) in the 13th century contrasted with the decline of Judaism in Tzarfat. Provence, cradle of the mystical interpretation of the Scriptures (Qabbalah), flourished as a centre of philosophy, the sciences and literature. The Jews were profoundly affected by the Shepherds’ Crusades (1251 and 1320) and by the persecutions after the Black Death in 1348. When Provence was incorporated into the kingdom of France in 1481, it expelled its Jewish population in 1498, thereby following the French example and a vast pan-European movement.

Yerouham ben Meshoullam de Provence (Languedoc 1290 - Tolède, 1350), Sefer Toledot Adam ve-Havvah, Sefer Mesharim, Constantinople, Empire ottoman, 1516

Theological controversies between Jews and Christians, frequent in the first centuries of Christendom, continued in medieval Europe, where they were usually conducted cordially. During the course of the 11th century, western Christianity stepped up its offensive against heresies in order to maintain its spiritual power. The attitude of Christian clerics to Jewish texts gradually changed from mistrust to outright hostility, and rabbinic literature became a prime target of anti-Judaism.

In 1239, Nicolas Donin, a converted Jew, went to Rome where, during an audience with Pope Gregory IX, he delivered an all-out attack on the Talmud, accusing it of being “immoral and offensive” for Christians, and “blasphemous” towards Christ and the Virgin Mary. The Pope promulgated a bull ordering the seizure of all copies of the Talmud in France, England, Aragon and Castilla, and the opening of an investigation of the content of the Talmud. King Louis IX, known as Saint Louis, was the only monarch to comply with this demand. Books were seized throughout France and taken to Paris, where a public disputation was held in the presence of the king and the queen mother, Blanche of Castille, on 25 and 26 June 1240. The trial of the Talmud dealt with the thirty-five accusations in Gregory IX’s bull, grouped into five themes: I. The value and authority of the Talmud, and the exaggerated importance it has for the Jews; II. The blasphemies it contains against Jesus; III. The blasphemies against God and morality; IV. The blasphemies against Christians; V. Errors, nonsense and absurdities.

The principal Christian protagonists of the debate were Eudes of Châteauroux, chancellor of the University of Paris, and Nicolas Donin. Four eminent rabbis spoke for the Jews: Yehiel ben Josef, head of the yeshivah (Talmudic school) of Paris, Judah ben David of Melun, Tosafist (commentator) and head of the yeshivah of Melun, Samuel ben Solomon, also known as Sir Morel, of Falaise, one of the most eminent French Tosafists, and Moses ben Jacob of Coucy, Tosafist and author of the Sefer Mitsvot Gadol. The Jewish clerk of the court was Nathan ben Josef, nicknamed the Official. Despite the oratory prowess and erudition with which the rabbis refuted the accusations point by point, the Talmud was found guilty. All copies (twenty-four cartloads of books, it is said) were publicly burnt in Paris, in present-day Place des Vosges, probably in 1242. The Jews attempted to rehabilitate their sacred texts. A few years later Pope Innocent IV agreed to re-examine the verdict, but a second commission, presided over by the Dominican Albert le Grand, merely ratified it in 1248.

Stèle funéraire, Paris, 1281

In the High Middle Ages, the Jews of Paris lived on the Île de la Cité. Due to the urban density and the tradition that Jewish burial places should be outside the city a cemetery was established at the foot of the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève on the Left Bank, near the former rue de la Harpe and rue Hautefeuille. On their return from their first exile, between 1182 and 1198 the Jews also had a cemetery between rue Galande and rue du Plâtre (now rue Domot in the 5th arrondissement). In December 1258, the Jewish community, represented by Bonne Vie, Croissant Morin, Croissant le Ceinturier and Hanin le Gainier, came to an agreement with the canons of Notre-Dame, affiliated with the Chapel of Saint-Aignan, regarding the payment of an annual tax of four livres parisis for this cemetery. Both sites were used until 1273. For unknown reasons, the community gave up the rue Galande cemetery, which regent Duke Philip the Bold retroceded to the canons. Only the cemetery in rue de la Harpe was maintained until 1306, when the Jews were expelled from France by King Philip the Fair. The land tax roll of 1292 mentions a sergeant by the name of Henri as guard of the Jewish cemetery.

Epitaphs from this cemetery were transcribed by scholars in the 16th century. Its remains were unearthed in 1849 during the construction of the Hachette bookshop on the corner of boulevards Saint-Germain and Saint-Michel. Seventy steles were allotted to the Musée de Cluny and three to the Musée Carnavalet. Other gravestones, dispersed in various buildings, were subsequently discovered. The dating of most of them (12th and 13th centuries) and their typology indicate that they are from the rue de la Harpe cemetery. However, a magnificent rabbinic stele engraved in 1364 comes from a third cemetery, created in the Marais in the 14th century.

We do not know how the cemetery was laid out since no comparable burial site has survived, but the steles were undoubtedly set upright in the ground on individual graves, in Ashkenazi tradition. The stones vary in form. The inscriptions sometimes follow ruled lines, like manuscripts. They are entirely in Hebrew and always begin with “This is the funerary stele of,” followed by the deceased’s full name, title (the word “rabbi” does not designate a rabbi but is an expression of deference), and the date of death, stating the day, week, (designated by the weekly reading in the Pentateuch), month and year. The inscription ends with the ritual phrases “who has departed to the Garden of Eden” and “may his/her soul be bound up in the bond of life.” None of the steles are decorated. Several French names (Flore, Belle-Assez) show a degree of symbiosis with Christian culture, also found in female Jewish first names in Provincia. These steles may include that of rabbi Yehiel of Paris, head of the Talmudic school, who took part in the debate on the Talmud in 1242, and those of his son and daughter.

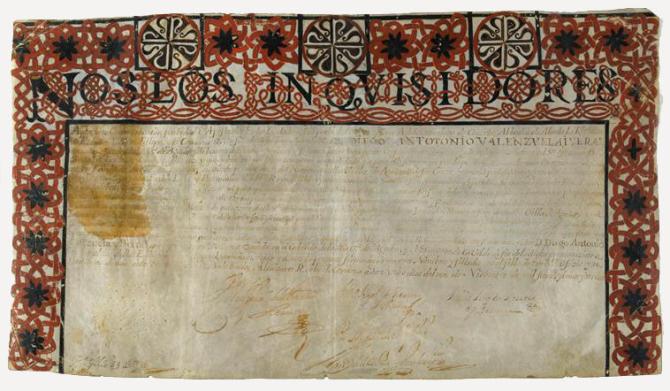

Nos los Inquisidores, Cordoue, 1723

On 31 March 1492, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castille signed the Alhambra Decree in Grenada expelling the Jews from their respective kingdoms, thereby putting a abrupt end to over a thousand years of Jewish presence in the Iberian Peninsula. On a religious level, this expulsion completed a process of national unification achieved politically by the union of the crowns of Castille and Aragon in 1479, and territorially by the fall of Grenada, the last Muslim enclave in the peninsula, in January 1492.

Catholic kings accused the Jews of inciting “bad Christians” to convert to Judaism in secret, and of being a source of contamination and propagation of Judaic heresy. The decree was in fact denouncing, without naming them, the “New Christians” (converted Jews or their descendants, encouraged in their practices by daily contact with Jews. To understand the 1492 decree one has to go back to the wave of massacres and forced baptisms inflicted on Jewish communities in Spain in 1391, compounded in the early 15th century by the vast propaganda campaigns that gave rise to the “Converso” category. The Converso question came to a head in the mid-15th century, when the first “pureblood” (limpieza de sangre) statutes, forbidding recently converted Christians (conversos) from holding office, were promulgated in Toledo in 1449 and from then on became a subject of fierce debate.

The decree deplores the inadequacy of the “remedies” implemented by Catholic kings to limit contacts between Jews and conversos: the decision of the Cortes in Toledo in 1480 ordering Jews to be separated into “barrios” outside the city walls, the expulsion of the Jews from Andalusia in 1483, and the establishment of the Inquisition in Spain in 1478. The 1492 expulsion thus completed a process of marginalisation and expulsion begun a decade earlier. The Inquisition, led by Tomás de Torquemada, played a crucial role in this decision. From 1481 to 1492 its tribunals tried some thirteen thousand New Christians, more than a thousand of whom were burnt at the stake.

The decree ordered Jews to leave their Spanish properties on pain of death before the end of July 1492, thereby forcing them to sell their possessions at a very low price. The only alternative was conversion. The secular clergy and the mendicant orders increased efforts to persuade Jews to renounce their faith. The rift this created amongst the Spanish Jews is epitomised by Isaac Abravanel (1437-1508), who chose exile, and Abraham Senior (1412-1493), chief rabbi of Spain, who accepted baptism.

Exiles left for North Africa and Italy or to Navarre and Provence, but most chose Portugal. In December 1496, King Manuel I of Portugal signed a decree ordering Jews and Moors to leave his kingdom before December 1497. However, loathe to deprive himself of their skills, he had them forcibly baptised with great violence. The Jews were expelled from kingdom of Navarre in 1498.

These expulsions set in motion a massive cultural and demographic displacement that profoundly Hispanicised the Mediterranean Jewish world.