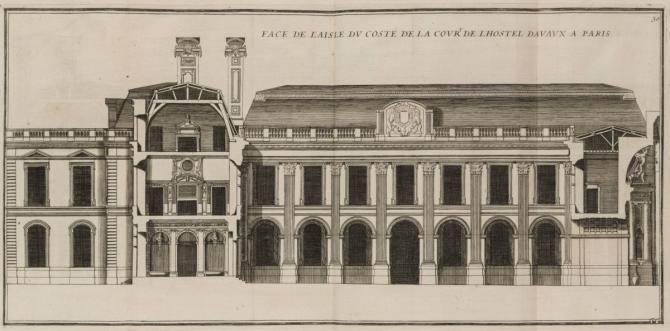

Elevation de l'hôtel d'Avaux

par Pierre Le Muet, 1647

Acquired by the City of Paris in 1962 as part of a plan to preserve the Marais quarter, the Hôtel de Saint-Aignan, built by Pierre Le Muet (1591-1669), is one of the jewels of 17th-century Parisian architecture.

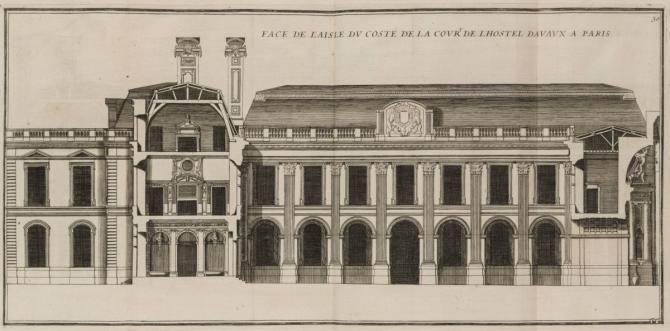

Elevation de l'hôtel d'Avaux

par Pierre Le Muet, 1647

The mansion was built from 1644 to 1650 for Claude de Mesmes, Comte d'Avaux, who represented Richelieu and Mazarin in the negotiations leading to the Peace of Westphalia (1648). The architect Pierre Le Muet (1591-1669), renowned for his ability to cater for all tastes (1623) and the quality of the châteaux de Chavigny, de Pont and de Tanlay (1638-1645), drew up the plans.

The mansion was built on a large, irregularly shaped plot, formerly occupied by the family residence inherited by Claude d'Avaux in 1642. Having demolished the former building, Le Muet opted for the usual plan for large aristocratic mansions, with the residence itself set back from the street, at the rear of a large, almost rectangular courtyard giving the impression it is square, and one perpendicular wing on the right (kitchen, servants’ room and dining room on the ground floor, and a large gallery on the first floor, like the Hôtel de Sully in its original state). A passageway led to a second, smaller courtyard where outhouses and stables had their own access to the street. Against the wall on the left, part of the Wall of Philip II Augustus (part of the city’s original fortifications), Le Muet built a false façade identical to that of the right wing to create an impression of symmetry.

Emmanuel Pottier,

La cour de l'hôtel de Saint-Aignan, vers 1910

When Paul de Beauvilliers, Duc de Saint-Aignan, bought the mansion in 1688, he divided the gallery into apartments, accessed by an exterior staircase partly jutting out over the north courtyard. He acquired a small adjoining plot of land to extend the right wing into the garden, also to house small apartments. He commissioned André Le Nôtre to redesign the garden with flowerbeds, an ornamental pond and trelliswork.

The mansion was confiscated by the Revolutionary authorities in 1792 and became the seat of Paris’s seventh municipality in 1795, and of the seventh arrondissement until 1823. It was subsequently divided into commercial premises of all kinds and storeys and mezzanine floors were added. After its purchase by Paris City Hall in 1962 and its listing as a historic monument in 1963, its gradual restoration, with lengthy interruptions, took more than twenty-five years. With the exception of the 1690 additions and a few errors (skylights on the courtyard side, first-floor ceiling lower than the window arches), the mansion’s restoration and the reconstruction of its staircase and roofs, completed in 1998, did much to restore the original splendour of one of the finest Parisian examples of the serene classicism known as Atticism during Anne of Austria’s regency.

Escalier d'honneur

Hôtel Saint-Aignan

The Italian architect Vincenzo Scamozi, travelling in France in the early 17th century, was surprised that even in large houses one entered via the stairwell (the Hôtel de Sully is an example of this). But around 1640 the vestibule, until then exceptional, became more widespread. Here, as in the Château de Maisons, a vestibule, nobly decorated in the antique style with alcoves and pilasters, precedes the staircase.

But although the vestibule survived 19th-century alterations, the staircase had been completely destroyed. All that remained were archaeological traces (the embedments of the steps in the walls of the stairwell and of the vaults supporting the landings, balusters and fragments of the wall string). Yet, with the plans published by Le Muet, these vestiges were enough to reconstruct the original staircase.

Le Muet’s design was a variation of the staircase invented by François Mansart, spectacular but unfinished at Blois, more modest but completed at Maisons. The flights only go up to the first floor. One reaches the second floor via a small staircase on one side, and the upper landing runs all around the stairwell, encircling the oval skylight and enabling one to see the stairwell’s domed ceiling from the ground floor.

The trompe-l'œil perspective on the dome is a modern creation inspired by a sketch, the only quadrature (except for the stage) proposed for the Hôtel d'Avaux, but explicitly annotated “not done.” It would not have been in keeping with the taste of Claude d'Avaux and Le Muet, the foremost Parisian exponent of Atticism, who preferred to leave the dome white.

Around 1640, the dining room became a more common feature of large Parisian mansions. The architect Le Muet skilfully placed it in the right wing, near the kitchen but separated from the service rooms by the passage leading to the north courtyard.

The dining room’s decoration, painted in grisaille, dates from the building’s construction, before 1650. This decor, not mentioned in ancient guides of Paris, had been covered over and forgotten. During the initial restoration work, it went unnoticed and was further damaged. It was discovered in a fragmentary state during the second, more careful phase of restoration. The symmetrical arrangement of its motifs could have enabled its almost entire reconstruction, but this would have been to the detriment of its original parts.

No written record of this commission has been found, but its very Roman style is reminiscent of the grisaille decoration of the gallery of the Château de Tanlay, painted in 1646 by Rémy Vuibert (1600-1652) under Le Muet’s supervision. Like Tanlay, it is one of the jewels of “Atticism,” the fashion for antique-style figures and ornaments, light, often monochrome colour, balanced compositions and figures with clinging drapery that triumphed in the 1640s after Poussin’s brief return to Paris. Rémy Vuibert was one of its great exponents.

Claude Mignot